questioned the reverence among Jews for the Balfour Declaration

and critically examines its roots and context.

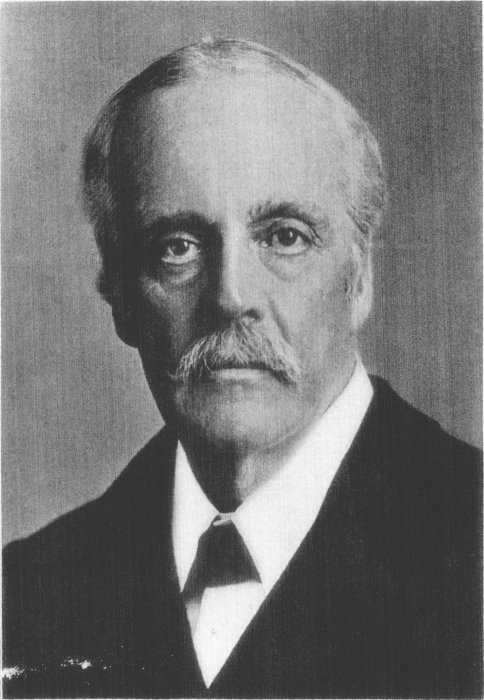

BALFOUR

2nd November 1917

Dear Lord Rothschild, I have much pleasure in conveying to you, on behalf of His Majesty's Government, the following declaration of sympathy with Jewish Zionist aspirations which has been submitted to, and approved by, the Cabinet:

'His Majesty's Government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of the existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or he rights and political status enjoved bv Jews in am other country.' I should be grateful if you would bring this declaration to the knowledge of the Zionist Federation.

Yours sincerely

Arthur Balfour

There's a moshav, a farming settlement, in northern Israel called Balfouria, and a Balfour Street in Tel Aviv. The Zionist Federation's headquarters in London is Balfour House. I knew a fellow whose parents had given him the forenames 'Theodor Balfour', after Theodor Herzl the founder of political Zionism and the right honourable James Arthur Balfour.

Yet this Balfour, as Prime Minister, introducing the 1905 Aliens Act in the wake of Russian pogroms, had spoken of 'the undoubted evils that had fallen upon the country from an immigration which was largely Jewish'. At that time the world Zionist congress accused him of 'open antisemitism'.

In 1917, asked to intercede with the Czarist regime for the removal of civic disabilities on Jews, Balfour refused, reportedly opining that: 'Wherever one went in Eastern Europe one found that by some way or another the Jew got on, and when to this was added the fact that he belonged to a different race and that he professed a religion which to the people around him was an object of inherited hatred, and that moreover, he was ... numbered by millions, one could perhaps understand the desire to keep him down...'

AN OLD TRADITION

Like others of his class, Balfour actually admired those supposed characteristics of Jews which set them apart. His Declaration was not just a ploy to send them elsewhere, but stood in a Christian tradition much older than the Zionist movement, which saw a happy coincidence between divine prophecy and material ambitions in the Middle East.

Already in the 17th century, when Cromwell readmitted the Jews to England the idea of restoring us to Palestine was discussed, seen as boosting prospects for the Second Coming and perhaps more immediately those of the English Levant Company. Fortunately Cromwell's first priority was bringing trade from the Netherlands to London, and the Jews of Amsterdam saw greater promise in the New World than in an ancient 'Promised Land'. Hence Menasseh Ben Israel explained to the Puritan parliament that we must be dispersed all over the world before Messianic prophecy could be fulfilled.

At the beginning of the 19th century Napoleon tried appealing to the Jews of Asia during his Syrian campaign, promising to restore a Jewish Kingdom. Then Palmerston, seeing French claims to protect the Maronite Christians, and the Czar asserting his interest in the Orthodox Christians, sought to trump them by instructing Britain's consul in Jerusalem to pay attention to the Jews. But in his wishful thinking that Jews would rally to serve British interests, Britain's Prime Minister wildly exaggerated Jewish cohesiveness and strength, as well as fervour for Palestine. He wasn't the last.

It was not until the First World War that Britain, no longer interested in shoring up the Ottoman Empire, but intent on dismembering it, was able to enlist the Zionist movement and to offer the prize of Palestine.

EUROPEAN ORIGINS

The heart of Zionism then was among the Jews of eastern Europe, specifically the Russian Empire with its pogroms and Blood Libel, where young Jews grew up between tradition, emigration and revolution. But its head was in the West, encountering disappointment with the liberal emancipation and assimilation of which others still dreamt. In Paris, the Viennese journalist Theodor Herzl had covered the Dreyfus trial. 'I achieved a freer attitude towards antisemitism, which I now began to understand historically and to pardon,' he wrote. 'Above all, I recognised the emptiness and futility of trying to "combat" antisemitism.'

The following year, 1896 he produced Der Judenstaat, proposing a Jewish state, and in 1897 presided over the first Zionist Congress, in Basle. He predicted - not altogether inaccurately as it happened - that in 50 years people would realise he had founded the Jewish State. That same year 1897 saw the founding in Vilna of a very different body, the Jewish Workers' Bund. Bundists believed Jewish workers must fight for their rights where they lived, not by seeking some Promised Land, but as part of the wider struggle for freedom, and a socialist future for all. What's more, they acted on this.

One of the most horrific anti-Jewish pogroms took place in Kishinev, in April 1903, encouraged by the Czarist authorities. The following month Herzl, with a mixture of naivety and cynicism, set out for St.Petersburg to meet the Czar's ministers Witte and Von Plehve. He offered to woo young Jews away from the socialists and help remove Russia's Jews, if the Russian government helped with Zionist aims for Palestine. Nothing came of this, for the Russian ministers had no influence on the Turkish Sultan. and Herzl could not control young Russian lews. At Gomel, that August, the Bundists were joined by groups like Poale Zion in organising resistance against a further pogrom.

In London, the previous year. Herzl had appeared before the Royal Commission on Alien Immigration, telling them: 'The Jews of Eastern Europe cannot stay where they are - where are they to go? If you find they are not wanted here, then some place must be found to which they can migrate...' The Zionist leader reassured establishment British Jews that his Zionism was not meant for them, but for their poor brethren fleeing eastern Europe, whose arrival in greater numbers would only generate antisemitism and undermine those established here. Lord Rothschild, who had been worried about what impression this foreign adventurer might make on Her Majesty's Commissioners, was eventually won over.

Another ally won, strange considering his racial prejudice about Jews, but befitting Herzl's admiration for Cecil Rhodes, was the imperialist Joseph Chamberlain. They shared the idea that Europe's unwanted poor and 'problem' people could be made useful settlers overseas. Herzl and Chamberlain travelled together to El Arish, to look at whether Jewish settlement at this gateway to Palestine might help guard Britain's imperial lifeline through Suez. Nothing came of this, still less of a subsequent British offer of land in East Africa, a non-starter with Russian Jewry. Herzl died in 1904. But the seeds of a relationship had been started.

A TANGLED WEB

On 16th August, 1914, shadowed but not intercepted by the Royal Navy, the German warships Goeben and Breslau arrived at Constantinople, where they were renamed and hoisted Turkish flags, and the crew were issued with fezzes. Before long they were shelling Russian Black Sea ports and Turkey was able to close the Dardannelles - Russia's only access to warm seas.

Worried as it had been by Germany's influence in Turkey, the drive east, and Berlin-Baghdad railway, the British government - or at least sections of it - may have secretly welcomed Turkey's entry into the war, and hoped to gain from it. But Allied forces, trying to force the Straits open suffered bloody defeat in an almost year-long struggle at Gallipoli. The British Empire's invasions of Mesopotamia (Iraq), and Palestine, assisted by Jewish spies and the Arab revolt, were no walkover.

The diplomacy was more complex. In November 1915 the British diplomat Mark Sykes and the Frenchman Francois Georges-Picot sat down to plan how the Ottoman Empire would be carved up after the war. This Sykes-Picot agreement, extended to bring in Italian and Russian ambitions, contradicted promises which Sir Henry McMahon had made to Sherif Feisal Husseini of Mecca, of an Arab kingdom in return for assisting Britain against the Turks. The Sykes-Picot agreement was secret, only published by the Bolsheviks after the October 1917 Revolution, when they seized documents held in the Russian Foreign Ministry.

British forces used Feisal's army to stifle an Arab government that emerged in Damascus, then ordered Feisal out so Syria could be handed over to the French, as per the Sykes-Picot agreement. But the British government wanted to keep its allies well away from Egypt, and the canal. Haifa was to be a British naval base, and the rest of Palestine to go into international trusteeship, to be decided.

Sykes, though originally prejudiced against 'international Jews', had already discussed with Herbert, later Viscount, Samuel and Rabbi Moses Gaster how British interests might be advanced by promoting Zionist aims.

With the world Zionist leadership left in Berlin, Chaim Weizmann, his work as a chemist valued by Britain's Ministry of Munitions, emerged as chief Zionist negotiator with British ministers. He was assisted by the Manchester Zionists, Harry Sacher, Israel Sieff, Simon Marks, Albert Hyamson and Co. They brought introductions to Liberal and Labour leaders, the Manchester Guardian and New Statesman, and Lloyd George, who replaced Asquith as Prime Minister in 1916. They set up a British Palestine Committee with Jewish and non-Jewish members.

Zionism had more powerful backers in the cabal of British imperialists advising Lloyd George, including Philip Kerr (later Lord Lothian), Lord Cromer, Leopold Amery, and Lord Milner, who had worked with Cecil Rhodes, and with Zionists, in South Africa, and drafted the final version of the Declaration issued by Balfour.

WHAT INTERESTS?

The war government was interested in using Zionism not just to cloak its claims in Palestine, but to win support for its aims from Jews, whose influence it exaggerated in Europe, Russia and America, just as it exaggerated Zionist influence among Jews. 'We might hope to use it in such a way as to bring over to our side the Jewish forces in America, the East and elsewhere, which are now largely, if not preponderantly, hostile to us,' explained a Foreign Office memorandum to the British ambassadors in Paris and Petrograd, dated 9th March 1916.

The election of the anti-war Socialist Morris Hillquit in New York, and Russia's slide toward its October Revolution (which British newspapers blamed on Jews) only accelerated the moves. The Foreign Office's Department of Information had set up a Jewish section in 1916, headed by Weizmann's co-worker Albert Hyamson. The War Office let Zionists communicate via its links to supporters in the United States.

When America's former ambassador in Turkey, Henry Morgenthau, set off on a mission ostensibly to assist Jews in Palestine - but actually to investigate reports that Turkish leaders wanted a separate peace -Weizmann was sent to Gibraltar to intercept him, and persuade him not to proceed.

In his book, Trial and Error, Weizmann tries to belittle Morganthau, suggesting the experienced diplomat was just trying to give himself importance by chasing an illusion. But whatever the real chances of peace, Chaim Weizmann and his British backers wanted to make sure it didn't happen before they had taken Palestine.

One member of the British government stood against the Balfour Declaration - the only Jewish member, Edwin Montague, who asked what authority he could have as HM Secretary for India, responsible for dealing with nationalists and Muslims, when HM Government proposed to declare his 'national home' was in Palestine. The rider added to the declaration, about Jewish rights and status elsewhere, owed something to his opposition, but not his alone.

Both the Anglo-Jewish Association and the Board of Deputies had expressed opposition. On 17th June 1917 Lord Rothschild wrote to Weizmann rejoicing: 'We have beaten them!', and arranging an interview with Balfour to tell him 'the majority of Jews are in favour of Zionism'. But the vote on the Board had only been 56-51.

If Zionism represents Jewish 'self-determination', as we are told by Zionists and those who listen to them, it is strange that it aroused such doubts among Jews and depended so much upon its perceived usefulness to an imperialist power.

As for what the Balfour Declaration called the 'existing non-Jewish inhabitants' - that is the 90% who were Arabs and were to become today's Palestinian nation, Balfour himself observed that the fine words about 'self-determination' used by US President Woodrow Wilson and the League of Nations would not apply to Syria, still less to Palestine: 'For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country... The four great powers are committed to Zionism and Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long tradition, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder importance than the desire and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land. In my opinion, that is right.'

Thus, even before the 'war to end wars' had ended, the scene was set in Palestine for almost a century of conflict, for which we still have to find a just end.

I am grateful to my friend Ted Crawford, of the journal Revolutionary History, for uncovering the document below, a statement originally published in the socialist paper The Call

'Jewish Social Democrats and Zionism'

a statement in The Call, 27th June 1918,

We have received the following statement from the Jewish Social-Democratic Organisation (BSP):

Since the publication of the War aims of the Labour Party, statements have appeared from time to time in the Socialist and Labour Press on Zionism and the Jewish question which display a total ignorance of the facts of the situation and call for their elucidation.

1. The so-called Jewish Socialist Labour Party 'Poale Zion' have no right to speak on behalf of organised Jewish labour, either in this country or any other. Here in England they represent no one but themselves. They are a body as small in numbers as they are in influence on the Jewish labouring population. They have never been authorised by the Jewish Trade Unions to speak on their behalf, and, if anything, these Unions are indifferent or even hostile to Zionism.

2. The same thing applies to America, where the organised Jewish Labour and Socialist movement (which is very powerful numerically, financially and in the influence it exerts upon labour conditions) has repudiated Zionism as a solution of the Jewish question.

3. But after all it was in Russia, and in the old Russia of the Czar, that there mainly was a Jewish question, and there, even before the revolution, the organised Jewish Labour and Socialist movement 'the Bund' has repudiated Zionism root and branch. Indeed, the Zionist movement was always a petty bourgeois movement, a movement among the small middle classes.

4. It will be seen therefore that the organised Jewish Socialist and Labour movement is everywhere opposed to Zionism - and for a simple reason. It is because Zionism cannot solve the Jewish question, if the question be viewed from a working-class standpoint. The emancipation of the working class can only be effected by the workers themselves, and in the country where they work and have their being. Now, what the Jewish workers require is to be placed on a par of equality of citizenship and rights in the widest sense in the countries where they happen to reside, and where they do so in large masses, such as Russia, Romania, America, and elsewhere. They demand not only political and civic rights, but also the right, if they so desire, to use their own language in the schools, in courts of law and other legislative and administrative institutions. To attain these objects Zionism is not necessary and is indeed harmful, inasmuch as if this movement were to obtain success among the Jewish masses it would tend to turn the attention of the workers from their economic and political struggles for the emancipation of their class into the paths of a petty and narrow nationalism and chauvinism.

5. Moreover, the experience of Belgium, Serbia, Greece and Ireland has shown how precarious is the existence and independence of the small states and nationalities, even where, as in the first three instances they were presumed to be sovereign. This experience is not such as would encourage the Jewish workers to try and establish a state of their own were this even feasible, which it is not. And it is not feasible because Palestine is not large enough to maintain the thirteen million Jews, and it is quite chimerical to imagine that these millions of Jews would or could break with the ties which bind them to the countries where they have lived and worked for generations and generations in order to emigrate to a country where they would find a civilisation and a climate which would be altogether uncongenial to their habits and the mode of living to which they have been used all their life. The Zionist movement is all the more impossible and ludicrous in Russia where the Jews, in common with all the rest of the nations resident therein, have at last found their emancipation from their common yoke of Czarism, and where the Jewish workers are eager to help in the building up of that great Republic.

6. Finally, on the grounds of the first principles of democracy, the Socialist movement must oppose the formation of a Jewish State in Palestine. In Palestine the Jews form an insignificant proportion of the population which mainly is Arabian, and which would bitterly and rightfully resent and fight against the robbery of their land. Let Palestine be free to determine its own fate and let it have its independence by all means, but it would be then an Arabian and not a Jewish State. The Socialist movement will support, of course, the freedom of colonisation in and immigration into Palestine for the Jews, but this it supports not only for the Jews but for all nationalities, and not only in Palestine but in all countries.

( The article on Balfour was originally published under the title 'Sale of the Century', together with the Jewish Social Democrats' perceptive 1918 statement, in JEWISH SOCIALIST, Winter 2007).